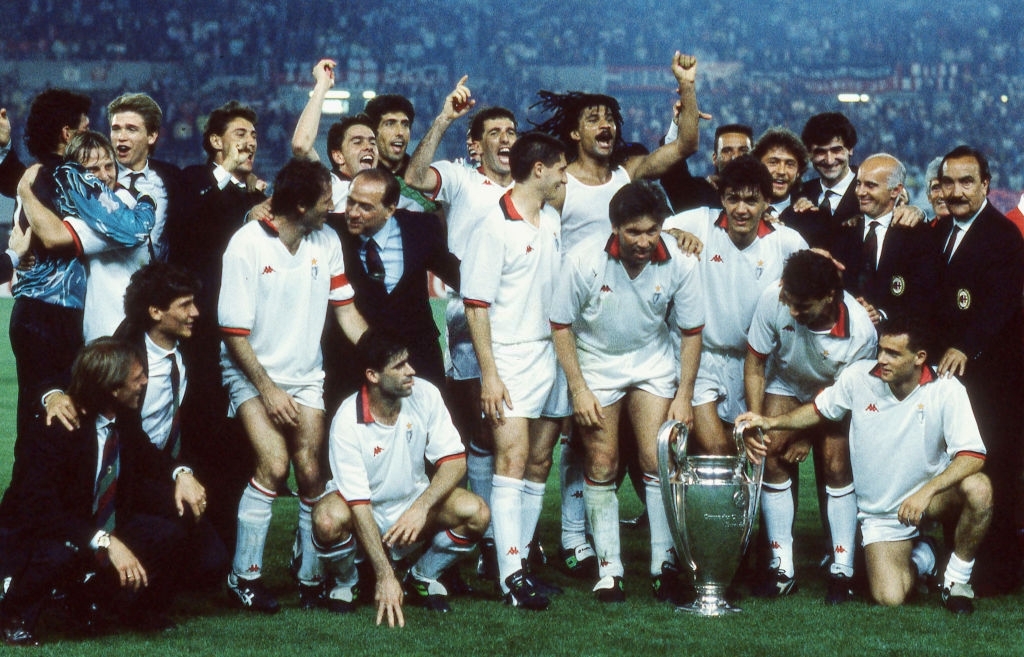

Sixty-four years old, fifty of which at Milan, twenty as a player, and fifteen as captain. It’s better to write these numbers in full; they make a stronger impression. Seven hundred and nineteen official appearances, six league titles, three European Cups, two Intercontinental titles won amid everything else.

He is the first Rossonero to enter the newly established Milan Hall of Fame, and on Tuesday the 22nd, his second book, “Ancora in Gioco” (Still in the Game) (written with Federico Tavola, Sperling & Kupfer, €19.90), a travel diary through places and people, will be released. In an era (of Milan) characterised by “shared leadership” (quote), he is a leader if there ever was one. Shy, quiet, even introverted. But a leader, authoritative and charismatic. Both on and off the field.

Ladies and gentlemen, Franco Baresi.

Why, two years after the release of your autobiography, “Libero di Sognare,” did you feel the need for a new book? Is it a way to celebrate your 50 years with Milan?

"The fifty years provided the impetus, and then the publisher insisted on a story that went beyond my twenty-year career as a player. However, there are another twenty-five years as a coach, manager, and now vice president, ambassador of the club. I wanted to recount the experiences I’ve had around the world in this last role, especially. Travel opens the mind, and in my case, it serves as a mirror reflecting who I have been and what I represent for others, what I have actually managed to transmit," he told La Gazzetta dello Sport.

How have travels opened your mind? Apart from the experience accumulated with age, what makes you different from the Baresi of 20 or 30 years ago?

"Learning is a choice. The knowledge gained from traveling has enriched me in every way. It was helpful to listen to people who know more than I do, and what I learned, I brought with me to work. If there’s one thing that makes me different from the man I was as a young person, it’s my attention toward others. The person always comes before the athlete, but it’s a perspective often overlooked. Rarely do we ask those in front of us how they are doing, if they are satisfied or even happy."

In the book, you write that in Manaus, Brazil, you met an archer, the first indigenous woman to make the national team, who told you about her difficult childhood. What was your childhood like?

"Equally difficult. I lost my mother at 13 and my father at 17. We siblings, three boys and two girls, had to grow up quickly. The people who remained by our side had the patience to wait for us, support us, and respect the times of formation and growth for each of us. My oldest sister, Lucia, acted a bit like a mother to us, and then the fortunate thing was that Beppe and I left Travagliato, the small town in the province of Brescia where we were born, very early—me at 14 and him even earlier. Changing our environment helped us find new energy and motivation: we had an opportunity that we knew how to seize, rolling up our sleeves. We also needed a bit of luck and a hand from above."

You are very religious.

"I grew up in a Christian family."

Have you ever doubted your faith?

"First of all, I have faith in the behavior of man, in the things he does. Then, when you have examples in your family, it’s natural to follow them. Even in religious matters."

Is the Franco Baresi who, as an adult, is few words, whispers more than he speaks, and keeps his emotions inside, a product of that faith and those losses?

"There’s a bit of everything in there. For sure, I grew up in a simple, united, rural family with healthy values. Establishing myself in Milan, in a completely different environment, was not easy."

How did you manage it? Baresi replied:

"Every child must follow their passion and believe in it wholeheartedly. I did. I had a path to follow, and I did. Then you need talent and the luck to find the right people who can bring out the best in you. The first day I entered Milanello, I was 14 years old: standing in front of a sports center that was already cutting-edge, it felt like I had entered Paradise. At 16 or 17, I played my first final in the Rossonero, in Viareggio: I took it as a sign of destiny. And indeed, many more came after that."

You write: "I have always maintained my identity as a dreaming child." Do you still dream today? (smiles)

"I always try to have goals and not to disappoint those around me. You can win or lose, but you must never lose your true self. That’s what I’ve always tried to do. And the thing that gratifies me most today is the fact that people from all over the world, meeting me almost 30 years after I stopped playing, show they recognize me for what I was and what I have demonstrated, trying to remain true to myself in every circumstance."

But did you remember that it’s been 50 years with Milan? Had you been keeping count? (laughs)

"To tell the truth, a few friends reminded me. Honestly, I think my story is hard to repeat."

You first donned the Rossonero shirt in ’74: how did it happen?

"In the simplest way: a scout received good reports about Travagliato, where I played, and came to watch us. Afterwards, he organized a trial. The first one didn’t go too well, at least for me. But they gave me a second chance, and I seized it."

When you arrived in the first team, you initially sat at the table next to Rivera.

"Before that, I had been a ball boy at Milan’s home games and had seen him play. Then I found myself next to him as a player. In the beginning, I struggled to address him informally. For me, he was a special person: he and Bigon protected me, pampered me."

Your first league title, the one with the “star,” came in ’79.

"On paper, Inter and Juve were much stronger. The title was built day by day, the group began to believe more and more, and we won thanks to an impressive consistency in performance."

Have you ever forced yourself, your way of being, because of football? For example, by raising your voice?

"That was never in my nature. I never yelled. There’s no need. When things weren’t working, I led by example with my daily behavior. Many small actions combined together that you end up transmitting to your teammates: to their philosophy, culture, and their way of working in training. The message is that the team and the club come first."

Why don’t you take a trip to Milanello today to transmit the values you embodied as captain? Baresi said:

"Because it’s not my role. It’s not my responsibility. But this summer, on tour, I met Fonseca, I was with the players, and I noticed that there’s always a great respect for me from everyone. The players of this Milan know who I am and what I did for Milan. They know the history, and that’s important."

If you were to take Rafael Leao under your wing, what would you tell him?

"I would tell him that he is lucky to be who he is. And not to forget it."

And to Theo Hernandez?

"The same. But I believe they know that, and they know they are in a great club."

What about the time an coach or teammate reprimanded you?

"You can’t… (laughs). My luck was finding coaches who always made me feel good, allowing me to work in peace. That’s why the person is more important than the athlete: for the second one to perform at their best, it’s essential to connect with the first, understanding their psychology."*

Have you ever cried for football? Baresi replied:

"It happened after some lost finals. And at my farewell match. Tears of joy, never: when you win, you don’t cry."

You write that you spent the first four years at Milanello. Who was your roommate?

"Actually, there were four of us in the room; we slept in bunk beds. One of them was Gabriello Carotti, an unfortunate talent. I still talk to him today."

In the first team, who made you laugh the most?

"Mauro Tassotti was funny, with his Roman accent. Di Canio was also amusing."

Who kept you up at night? Baresi said:

"I didn’t change many roommates: at first, I had Colombo, then Tassotti, and then I was alone. You know, I was the captain…"

Of your coaches, to whom do you feel grateful?

"As a kid, I had teachers like Annovazzi, Galbiati, and Zagatti. Then, for 15 years out of 20 in the first team, I had Liedholm, Sacchi, and Capello. Liedholm was unique: ironic, with a great personality, he gave you the right space to work calmly. He made me debut in Verona in ’78, telling me, “go and play like you know.” He meant I should play as I had been used to in the Youth Sector, but it wasn’t exactly the same thing… Sacchi’s Milan was young, curious, and daring, and he managed to involve us in his idea of football. We had all won little or nothing, so we were willing to learn something new. The first training session was immediately very intense: by the end, we were tired and aware that something was changing, but for the better. Capello found a mature team; he was more of a manager than a revolutionary."

The architect of the great Milan of those years was Silvio Berlusconi.

"He was the true innovator. I will never forget the helicopters at the Arena in July ’86. He had just become president and wanted to give a shake-up, a strong signal not only to the Milan environment but to the whole of Italian football."

Which teammate didn’t you believe was so strong, but was?

"I prefer to mention one who could have done much more given the talent he had, had he not arrived at Milan at the end of his career with various physical problems: Paulo Futre."

And who, on the contrary, didn’t do justice to their talent?

"Again, I prefer to answer that I was very sorry when Paolo Di Canio left Milan."

The match you would replay a thousand times? Baresi replied:

"If we’re talking about the ones I won, Napoli-Milan 2-3 in ’88, which practically handed us the league title, allowing us to open a cycle, and Milan-Real 5-0, which brought us to the Champions Cup final after twenty years."

What feeling from your twenty seasons in the first team would you pay to relive?

"The entrance onto the pitch when you emerge from the tunnel and face the wall of crowds at important matches."

You write in the book: Milan is passion, style, sacrifice, and success. Are these values that you find in the current team?

"These are values that encompass the history of the club and must be remembered. There is no Milan of today or yesterday; it is simply Milan: by its nature, Milan always aims for the maximum. We must remember this and behave accordingly."

You have coached the Primavera and Berretti teams: would you be able to adapt to the football and players of today, who are different from those of your time?

"Different how?"

Because today they have more knowledge, tools of all kinds, and even more distractions.

"The world has changed, but I’m sure that a football player knows that the center of their activities and interests must continue to be football."

This book is a reminder of travels: Brazil, the United States, Algeria, Israel, Iran… Which one left the biggest impression on you?

"Brazil. For the way of life of the people and the opportunities it can offer you. And also for its football, of course."

You’ve traveled the world: with what is happening globally, to the political leaders who are warring, what image among the many that you have imprinted in your memory would you give them to convince them to stop?

"The one of the children with whom we, from the Milan Foundation (Fondazione Milan), played in the streets of Lebanon."

As captain, the longest-serving Rossonero, what have you been most proud of?

"The satisfaction felt when the team played well and won."

Does friendship exist in football?

"I’ve found it. I won’t name names, but I’ve found it."

You write in the book: you must aim for the sky to hit the ceiling at least. Have you succeeded?

"I am happy with what I’ve had. I can’t complain."

To a twenty-year-old who has never seen you play, how would you explain who Franco Baresi was?

"I would tell him to go look at the trading cards… Seriously: I would tell him that I was a player who is part of Milan’s history."